A few months ago I spent a weekend with friends on the Beara Peninsula in West Cork. On our way from Glengarriff to Castletownbere we drove along the base of the bleak looking Hungry Hill. It’s the highest mountain on the peninsula. During our few days we visited Allihies, Eyeries and Bere Island, as well as the remains of the two Dunboy Castles close to Castletownbere. One of the castles was a seat of the O’Sullivan Beare and the other, which we were told was Puxley Hall, was that of the later owners of a large part of the peninsula. We talked about the mines once owned and operated by the Puxleys and the connection with Daphne du Maurier’s novel Hungry Hill, published in 1943.

When I got home I ordered a copy of Hungry Hill (from an Irish bookshop). The edition I got had an introduction by Nina Auerbach and it informed me that du Maurier ‘claimed to have appropriated the Brodricks [subjects of the novel] from the Irish ancestors of her friend Christopher Puxley’. This she certainly did. Having ploughed through the gloomy novel, I was left dissatisfied. However, I wanting to know how much of the story was that of the real Puxley family and how much was poetic licence.

Du Maurier used an imagined rivalry between her mine-owning family, the Brodricks, and the socially reduced Donovans who are the vengeful descendants of the original Irish owners of the property now enjoyed by the Brodricks. Evidently the Donovans represent a branch of the O’Sullivans, supposedly descended from O’Sullivan Beare whose ruined castle of Dunboy is just a few hundred yards from the new (and ruinous) Dunboy Castle built by the Puxleys.

I doubt there was an opportunity for du Maurier to visit the Beara Peninsula between the first time she apparently heard of the Puxleys and the publication of her book, and it shows in the writing. Her way of describing people and situations in Ireland is very foreign, as if she were a British visitor to India during the Raj. Despite that, she gives vivid descriptions of the views from Dunboy Castle. Perhaps Christopher Puxley gave her detailed information on that aspect. Perhaps she saw photographs. She also bestows the Brodricks with an abiding love for the fictionalised Dunboy Castle, Hungry Hill and Bere Island.

The novel is very uneven, with mundane passages followed by detailed and descriptive ones. After a while it’s obvious that something momentous it about to happen when the prose improves. Most of the characters are unlikeable so it’s not particularly upsetting when they die before their time. But you can empathise with some of them or even feel for the loneliness of Wild Johnnie Brodrick, so Daphne does weave a good story in spots. Unfortunately, the unrelenting tragedies are depressing. There is little joy in the novel and any such joy is determined not to last.

Of course, Morty Donovan put a curse on the Brodricks, so bad things are bound to happen. More often than not there is a descendant of Morty involved in orchestrating the bad things. Jack Donovan worms his way into the affections of the friendless Wild Johnnie and throws his sister Kate in his way. Even the local priest connives with the Donovans in their fleecing Wild Johnnie of his money. The natives just cannot be trusted.

The most irritating element of the story is that du Maurier and her characters invariably refer to travel between Ireland and Great Britain as going ‘across the water’. She must have been told that this was an expression, but she uses it trillions of times and employs no other description. The inlet or cove in front of the castle is called ‘the creek’. Is that an expression in West Cork? Before writing Hungry Hill, Daphne had been working on the Cornish tale of Frenchman’s Creek, so that may explain the term. Towards the end she has a Brodrick family member say that he is drinking the ‘spirit of the country’, meaning Irish whiskey, but du Maurier uses the Scottish spelling, whisky. All right, she didn’t research her subject very well and she was writing the novel in England in war time, with no Google to help her. Such mistakes may be pardoned.

One strange aspect of her creation is the changing of place-names. Apart from Hungry Hill, London, Oxford and Nice, every place has its name altered. It is understandable that the surnames Puxley and O’Sullivan were changed, as the novel was based on a real family, but changing the place-names added nothing to the anonymity as they can easily be identified. For a start off, Hungry Hill is an actual mountain on the Beara Peinisula. Dunboy becomes Clonmere; Castletownbere becomes Doonhaven; Bere Island becomes Doon Island; Glengarrif Castle becomes Castle Andriff; Bantry Bay becomes Mundy Bay; Cork becomes Slane; Swansea becomes Bronsea; and Tenby becomes Saunby.

Du Maurier misappropriates Hungry Hill for the site of the Brodricks’ mines. The first mine John L. Puxley opened, in 1813, was Mountain Mine, but that mountain was on the western extremity of the peninsula, as the Allihies Copper Mine Museum indicates. Hungry Hill was not mined, but it was a distinctive mountain with a curious name. The fact that it was visible from Dunboy Castle must have been brought to Daphne’s attention and presumably the name inspired her imagination. As I said, she cannot have been to the area before she wrote the story, unless she knew Christopher Puxley before the Second World War.

It seems that she first met Christopher as a result of the war. Her husband was a high ranking army officer and, apparently, when he was given command of the 128th Infantry Brigade in 1940 she and their children moved to Hertfordshire to be near him. According to A History of Preston in Hertfordshire, Hill End, they found accommodation as paying guests at Hill End, Langley End. The owners of the property were Christopher Puxley and his New Zealand-born wife Paddy. Their formal names were Henry Waller Lavallin Puxley and Naumai Kathleen Clephane (née Guinness). For whatever reason, they were Christopher and Paddy to their acquaintances. Perhaps Daphne knew them before, but it seems unlikely. In any case, she worked on the writing of Frenchman’s Creek at Langley End and after its publication in 1941 presumably she began Hungry Hill. The Hill End history linked above indicates that she left there in 1942 when it became apparent to Paddy that Christopher and Daphne had become too friendly.

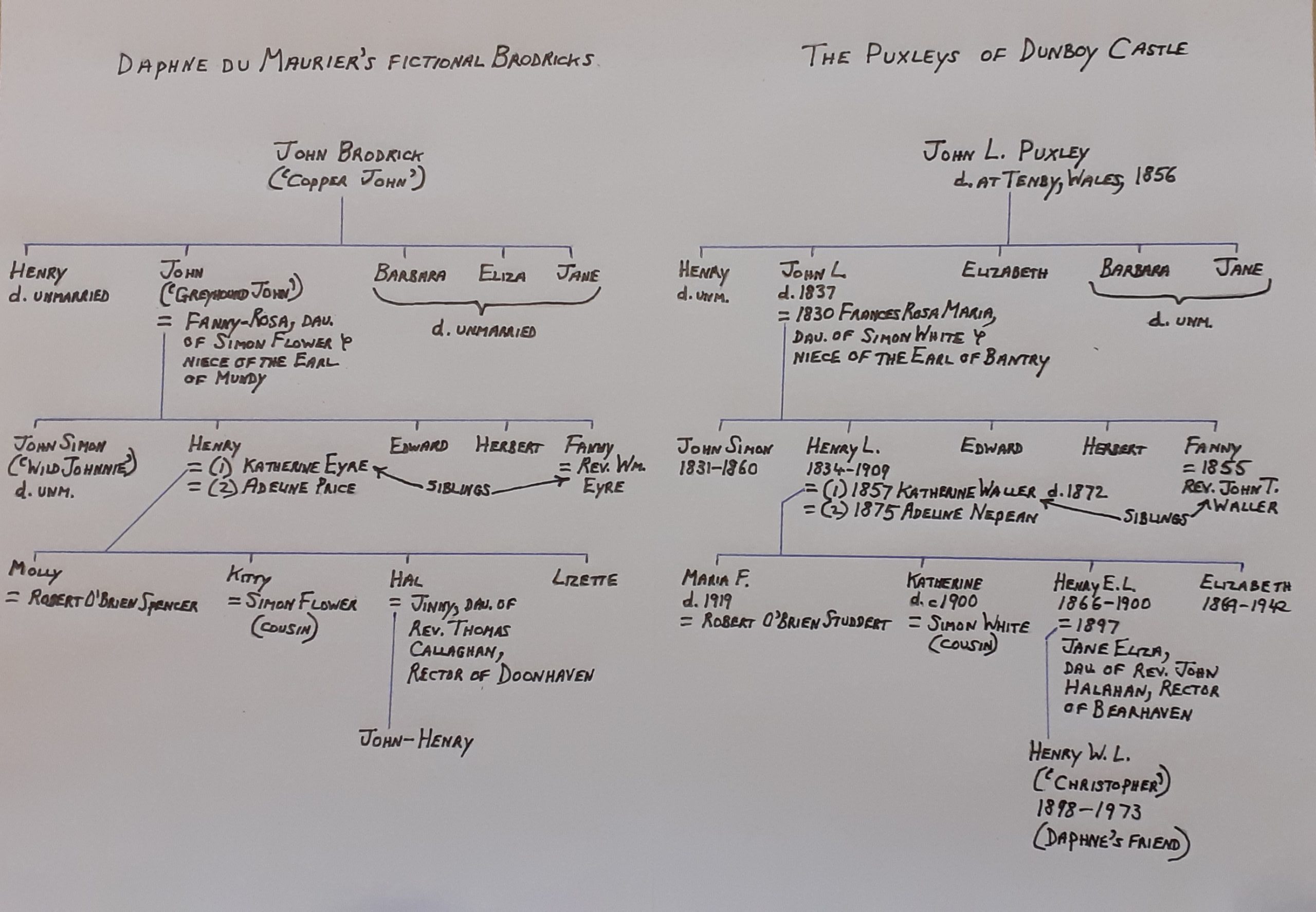

As I said, Hungry Hill was a disappointing read but it piqued my curiosity about the real family on which the Brodricks were based. To my amazement, I found that after changing the surnames and the place-names, du Maurier barely disguised the forenames of the Puxleys she chose as characters (see the sketch pedigrees below for comparison). There were other family members she omitted from her story. Christopher, his mother and his aunt Elizabeth were the only real characters still alive about the time when Daphne began writing the book, and Elizabeth died in March 1942. Regardless of whether there was anyone about who might initiate a libel case, it would be bad form to use someone’s family as a pattern for such a fictional brood as the Brodricks. There was good reason to hide the identity of the family but when she was doing so why did she use such a thin disguise?

And do the events in the novel mirror reality? Well, when Christopher was aged two his father, Henry, died at a young age. However, he died at Godmanstone Manor near Dorchester in England and not at the hands of a vicious Donovan at the abandoned mine in West Cork. Henry’s mother Katherine also died prematurely but not in childbirth. Her youngest child was three at the time and the cause of death was phthisis, which she endured for ten years. This may explain why the fictional Dr. Armstrong kept talking about the fictional Katherine being not strong enough to bear children. If she suffered from phthisis for a decade and bore three children during that time it must have been some wasting disease other than tuberculosis. Incidentally, the real Katherine’s death was recorded by one Dr. P.A. Armstrong.

Three years after her death, Katherine Puxley’s husband, another Henry, married a woman named Adeline, as did her fictional husband. But was the real Adeline a manipulative Lady Macbeth / Wicked Stepmother just like the fictional one? Then there is Katherine and Adeline’s mother-in-law, Fanny-Rosa Flower, or in reality Frances Rosa Maria White. It would appear that the real woman was dead by 1858, so her alter ego who in later life became a gambling addict in the south of France sprang straight from du Maurier’s imagination. I would guess too that Fanny-Rosa’s scandalous sister Matilda was invented by Daphne. Matilda was only referred to in the novel, she never appeared as a character but her unconventional situation was mentioned on and off. Here is what the fictional Dr. Armstrong thought of Fanny-Rosa’s father’s indulgence:

… but when he allowed his young daughter Matilda to elope with a cobbler from the village, a fellow already married, and invited her to live with her lover in the lodge of Castle Andriff and have one baby after another, then Doctor Armstrong considered, a man such as Simon Flower was a menace to the country that had bred him. He could not understand how the old fellow could hold up his head in society, but then society was very different here from what it was the other side of the water.

Rather than Armstrong, this is du Maurier speaking and with the voice of a British visitor to the Raj, but she had not visited the Beara Peninsula or immersed herself in nineteenth century Irish society. To her, the gentry in Ireland were an inferior version to those ‘across the water’. What is more glaringly obvious in her lack of knowledge of the country is the omission of even an oblique reference to the Great Famine. It happened while her fictional Brodricks were living at Clonmere Castle in close contact with their tenants, and flitting over and back to Wales. It is a gaping hole in the story.

I wonder if Daphne did any historical research for her novels. Was all the blarney in Hungry Hill fed to her by Christopher Puxley? Or did it spring from her outsider’s view of that strange place across the water? Perhaps it was a mixture of both. However, for the structure of the Brodrick family and their names, I am convinced that du Maurier was introduced at Langley End to the entry on the Puxleys in Burke’s Landed Gentry of Ireland, 1904 edition. The entry is a snapshot of her subjects and the period of her story. The fact that it is light on detail and omits certain dates allows Daphne to imagine Fanny-Rosa gambling away in Nice decades after her death. It is a novel, but one that uses the lightly camouflaged names of real people and projects on to them fictional emotions and actions that aren’t exactly flattering.

Nice one Paul. Does not inspire me to want to read the book, but interesting to see the research you have done on the connections between it, the Hungry Hill, the O’Sullivan Bearas and the Puxleys. Very interesting.

Thank you Orla – yes, skip the book. I did all the slogging in that regard and I don’t recommend it.

She deliberately omitted the Famine because it would have robbed her English settler family of any sympathy. The descendants of Longfield of Cork did the same in their books, as their ancestor was a reviled landowner famed for evicting his starving tenants at the height of the Famine. Hungry Hill is the site of a mass starvation event, of farmers who walked down the hill in search of food, and when no one provided any, they died together en masse, like other places with hunger marches in Ireland.

Very interesting and moving.

Hats off to you Paul. Your valiant grapple with du Maurier’s Hungry Hill has been so worthwhile. You’ve produced a unique blend of historical analysis, literary criticism and genealogical research. Not only have you thrown an interesting light on this novelist’s modus operandi and Anglocentric attitudes; you have also given us another fascinating perspective on the history of the beautiful Beara peninsula.

Hats off to you Paul. Your valiant grapple with du Maurier’s Hungry Hill has been so worthwhile! You’ve produced a unique blend of historical analysis, literary criticism and genealogical research. Not only have you thrown an interesting light on this novelist’s modus operandi and Anglocentric attitudes; you have also provided us with another fascinating perspective on the history of the beautiful Beara peninsula. Bravo!

Many thanks Cora. The exercise taught me a lot about the area.

I found this research very interesting as I have a connection to the Puxley family. My great-aunt was Janet Lavallin-Puxkey, married to John, brother of Christopher. My Great-Aunt collaborated with Margaret Forster when she was writing Daphne du Maurice’s biography. I inherited her book collection many of them signed. I always loved her novels as a child !

Hello Lucy, thank you for your interesting comment and apologies for not replying sooner. I’ve been neglecting my blog for quite a while but I’m back to it now. It’s very nice for you to have your grandaunt’s book collection.

Have the book and tried to read it a few times but lost interest. Thanks Paul for the research and insights. Think I will put it back on the shelf.

Thanks Donal and sorry for the tardy reply. I’ve been distracted from the blog for a long time but I’m back to it now.