A hundred years ago this very day my grandfather, Joseph Gorry, reached the zenith of his amateur golfing career. Very probably for him it felt like failure. The events of that day became the stuff of golfing legend in the family. His daughter, Joan Gorry, was proud of his achievement until her dying day, ninety years later. But her pride was tinged with resentment about the circumstance in which he lost the final of the Irish Open Amateur Championship on 8 September 1921.

When we look back on the turbulent years in Ireland following the Great War, it is difficult to imagine business as usual. How was that time of upheaval conducive to the staging of championship sports events, especially ones which aimed at attracting overseas competitors?

Belfast News-Letter, 7 Sept. 1921

The War of Independence started in January 1919 and lasted until July 1921. In May 1921 separate elections were held for ‘Southern Ireland’ and ‘Northern Ireland’, and on 22 June the Northern Ireland parliament was opened by King George V. Following the truce that ended the War of Independence on 9 July, the ‘Southern Ireland’ parliament met as Dáil Éireann on 16 August. It was not until 6 December 1921 that the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed in London. It is important to remember that, like the more recent ‘Troubles’ in Northern Ireland, the incidents of what became known as the War of Independence were spasmodic: it was not a constant and all-encompassing phenomenon.

In May 1920 the [British] Ladies’ Amateur championship was played on Royal Co. Down’s famous links course in the resort town of Newcastle. The scene was dominated, as it is today, by nearby Slieve Donard, the highest mountain in Ulster. Competitors came from throughout Great Britain and Ireland, as well as Canada and the USA, and the winner was the great Cecil Leitch.

Writing in the Belfast News-Letter, the golf correspondent James Henderson (‘J.H.’) said that the championship was held ‘under circumstances unparalleled in any similar event’. He commented that ‘nothing occurred to mar the pleasure of the players and their friends’ and that it was doubtful if many of the visitors were ‘aware of the activities of the spoil-sports who, posing as “patriots,” carried out some of their nefarious exploits within easy distance of Newcastle’. He added:

If the “patriots” hoped to impress the British and overseas visitors with the power of Sinn Fein, they failed. Golf is far more absorbing, as news, than the burning of empty police barracks.

My grandfather’s big day came sixteen months later, at the same venue. By September 1921 this area of the country was part of the three-month old political entity of Northern Ireland. The championship final was played over 36 holes – 18 in the morning and 18 in the afternoon, with a break for lunch in between. It was contested between two surprise packages – D.W. Smyth and Joseph Gorry. To put it crudely, they were a Presbyterian from the North and a Catholic from the South. At the end of the morning’s 18 holes, Gorry, the southern Catholic, was five holes up. The general opinion was that he had an unassailable lead. But the real drama took place in the afternoon when, according to Gorry family lore, the usual gallery of spectators was reinforced by a crowd with little interest in golf.

The Finalists

At that time the competitive amateur game was pursued by players for decades. It was extremely rare for an amateur to become a professional, and the status of amateur golf was as prestigious as that of the professional game. That said, it may be surprising to hear that the 1921 finalists were both in their mid-40s. Neither of them was going to be the oldest ever winner of the championship. Charles Palmer of England had already secured that record in September 1913 at the age of 54. However, the combined ages of the 1921 finalists may constitute a record.

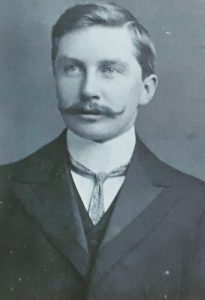

Joe Gorry c1923

In the Belfast News-Letter on 13 September 1921, James Henderson mentioned that my grandfather was familiarly referred to in golfing circles as the ‘old man’. Henderson suggested this was because of ‘his white hair, and set figure’. In fact, David Wilson Smyth was 17 months older than Joseph Gorry. Smyth was born on 12 November 1876, while Gorry was born on 29 April 1878, so they were 44 and 43, respectively, when the final was played.

D.W. (or Wilson) Smyth was a linen manufacturer living just outside Banbridge, Co. Down. In 1921 he was Captain of Royal Co. Down Golf Club, the venue for the championship. Before then he had not featured in the closing stages of the Irish Open Amateur, but he had done so in the Irish Close championship, being semi-finalist in 1907 and 1909.

Belfast News-Letter, 6 Sept. 1921

Joe Gorry was a pharmaceutical chemist living in Naas, Co. Kildare. He began playing golf at Co. Kildare (now Naas) Golf Club when he opened his shop in the town in 1902. He started competing in championships not long before the outbreak of the Great War. He earned a reputation for being ‘hard to beat’, but also for ‘slow play’. He was a tenacious match-player and some of his best opponents found him hard to shake off. Before that day in 1921, he too had not featured in the closing stages of the Irish Open Amateur. However, he had reached the quarter-finals of the Irish Close on three consecutive occasions – 1914, 1919 and 1920 (the Great War intervening between the first and second). In each case he was beaten by the eventual champion: Lionel Munn (by 4/3), Ernest Carter (1 hole) and Charles Hezlet (3/2). All three were players of the highest calibre.

The Second Eighteen

As mentioned already, after the morning round Joe Gorry was 5 up on Wilson Smyth. James Henderson’s report in the Belfast News-Letter is the one followed here. His account of the morning round stated that Smyth had lost ‘his great form of the previous day’, while Gorry ‘was much as usual – steady, but uninspiring, sure but painfully slow’.

In the afternoon there was no change until the 4th, when Smyth won the hole. On the 6th Gorry ‘played a remarkably clever chip, which he pluckily followed up by holing his putt for a 3’. However, Smyth got down in 2 and this ‘seemed to restore his confidence … for his golf for the rest of the round was really good’. At the same time Gorry ‘seemed to tire a bit, and, like many others, felt the heat, which at times was oppressive’.

Gorry was only two up at the 9th (or 27th of the 36 holes). He lost the 10th but they halved the next two holes and then Gorry won the 13th, the only hole he won in the afternoon.

Then a surprising thing happened. Gorry, a model of steadiness and machine-like golf, completely and hopelessly “duffed” his tee shot into a sand pit at the 14th (or 32nd.). His recovery was good, and he sank an excellent putt for a 4, but Smyth … got his 3, and reduced the lead again to one.

The match was squared at the next hole and Smyth went 1up for the first time at the 16th. The 17th was halved.

Amid a tense silence, the players drove off to the last hole, Smyth getting a longer shot. There was little to choose between their seconds; but Gorry’s approach was short and to the left, while Smyth played a perfectly judged run-up which finished just five feet past the pin. Gorry’s chip shot was not quite “dead” and the match was over.

Henderson’s report mentioned that the spectators were ‘numbering fully 1,000’, but he made no reference to any untoward behaviour from them. The Irish Times correspondent mentioned ‘the big, if somewhat unmanageable, gallery’. The Freeman’s Journal ‘special representative’ (possibly Cecil Barcroft) was a little more descriptive:

Henderson’s report mentioned that the spectators were ‘numbering fully 1,000’, but he made no reference to any untoward behaviour from them. The Irish Times correspondent mentioned ‘the big, if somewhat unmanageable, gallery’. The Freeman’s Journal ‘special representative’ (possibly Cecil Barcroft) was a little more descriptive:

He [Gorry] had not the best of luck, however, and the too close attention of the unmanageable crowd, together with the continual yelling and shouting of flag waggers was not to his liking. It was as bad for one as the other, but naturally the crowd wanted the local man to win.

The following week James Henderson, in his ‘Golf and Golfers’ column in the Belfast News-Letter, commented on two aspects of Joe Gorry’s play that he suggested contributed to his downfall. He suggested that the strong lead encouraged Gorry to ‘play for halves’, adding:

There is no more difficult policy to pursue for, as soon as it is adopted, the power and energy needed for winning holes seem to vanish, and struggle as he may, even the most skilful of golfers is practically unable to summon again his “will to win”.

The other aspect mentioned by Henderson was Gorry’s deliberation over each shot. He said ‘he … derives no benefit from the elaborate survey of the lie, line, stance and other circumstances of the shot in which he indulges …’. Henderson also noted ‘… I am only confirmed in the opinion I expressed here … after the Close Championship at Castleknock, that his laborious and painstaking ways are a hindrance to him rather than a help’.

True enough, on 27 May 1920 in his account of the Hezlet / Gorry quarter-final of the Irish Close at Castlerock, Henderson wrote:

Gorry has made a fetish of deliberation. He is slower even than he was, and although golf is a game in which the cautious player usually enjoys the advantage, there are times when such tortoise-like methods as those adopted by Gorry defeat themselves …

The Gorry Legends

For a failed golfer, I have an extraordinary interest in Irish golf records. My grandfather’s career and his day in the sun contributed greatly to that interest. All the same, over the years I have had to peel off a few layers of the legend to see the Irish Open Amateur of 1921 in perspective.

The Irish Open Amateur was a prestigious championship

It was indeed a prestigious event from its inception in 1892, with the likes of John Ball and Harold Hilton winning on a number of occasions. Lionel Munn’s three-in-a-row wins in 1909-1911 contributed to his reputation as Ireland’s first great amateur. Even after the Great War many top British amateurs competed in it in 1919, but the political situation in Ireland took its toll on the championship. While there were 132 competitors in 1919, there were only 83 in 1920. Of these, only 16 were from over the water – one from Scotland and fifteen from England, including the holder, Carl Bretherton. In 1921 there were only 72 entrants altogether, with just a smattering of non-Irish competitors. This was the lowest number since 1909. It has to be admitted that 1921 was the event’s least representative staging from its inception to the outbreak of the Second World War.

Joe Gorry was never selected for an international match

There was a long held grievance that my grandfather’s ability was never recognised with selection to an Irish team. The first official international match in which Ireland competed was against Wales in 1913. This was before Joe Gorry could have been a contender for a place on such a team. The next international Ireland contested was ten years later. This involved matches against the English Midlands and Wales. It was between these dates that grandfather might have been considered for international honours, but the possibility never arose, so there are no grounds for the grievance.

For several years the Irish Professional and Irish Amateur Close championships were held one after the other at the same venue. Beginning in 1908, a friendly match was organised most years between the professionals and the amateurs. In 1914 the championships were at different venues and there was no match. In 1919, when competition resumed after the Great War, so too did the match. Joe Gorry was on the amateur team, albeit one of 20 players on the side. In 1920 the usual match was replaced by one between the amateurs of ‘North’ and ‘South’. There were 14 a side and Joe Gorry was on the ‘South’ team. So, it cannot be said that he was overlooked for friendly matches during the period when there were no internationals.

Joe Gorry was bustled out of a victory

Well, the Gorry legend stated that a non-golfing element descended on the links for the afternoon round, that it was sectarian and intimidating, and that Joe Gorry’s play was adversely affected by this presence. Almost all accounts of the final made no reference to any such disruption. Perhaps it was considered potentially inflammatory to make any comment. The Irish Times mentioned the gallery as ‘somewhat unmanageable’. The Freeman’s Journal was more descriptive, referring to ‘the continual yelling and shouting of the flag waggers’, while suggesting that it was equally difficult for both players. As this was three months after the establishment of Northern Ireland, I can only imagine that the flags were Union Jacks and that they unsubtly conveyed support for the Union rather than Smyth’s play. I must emphasise that the Gorry golfing legend never contained any suggestion that Wilson Smyth condoned unsporting behaviour, and there was no animosity felt towards him.

After 1921

Golf and family history are often intertwined. On that day in September 1921, Wilson Smyth became Irish Open Amateur champion. In 1923, at the age of 46, he became an Irish international, playing matches against Wales and the English Midlands. He was on international teams in 1927 and 1930, and he was playing captain in 1931 and 1933. Smyth served as President of the Golfing Union of Ireland from 1932 to 1936. He died in 1953. His daughter Moira Smyth (1914-1990) became an Irish international in 1947 and played in the Home Internationals every year from then until 1959. She was Ulster champion in 1951, 1958 and 1959, and was semi-finalist in the Irish Close four times. She served as President of the Ladies’ Golf Union (now absorbed into the Royal & Ancient) for 1976-1978. In 1979 she presented the Smyth Salver for the leading amateur in the Women’s British Open. Since then the event has become a ‘Major’ in women’s professional golf. Last month Louise Duncan of Scotland became the most recent recipient of the Smyth Salver.

Joe Gorry c1903

Joe Gorry c1917

After 1921 Joe Gorry was a quarter-finalist in the Irish Open Amateur in 1923 and 1929, and a quarter-finalist in the Irish Close in 1924. At the suggestion of the international J.D. MacCormack, he joined Hermitage Golf Club in order to represent it in the Senior Cup, and he was on its winning team in 1926. The first Irish Open was staged at Portmarnock in August 1927 and 49 year old Gorry was a competitor. He made the halfway cut and completed the entire 72-hole tournament, though he finished 51st, with only one competitor behind him.

Joe Gorry in old age

My grandfather died in 1960. Seven years later his granddaughter Hilda Gorry represented Ireland for the first time in a girls’ international. In 1970 her sister Mary also became a girl international and the following year she gained her first full international cap. In 1975 she won the Irish Ladies’ Close title and repeated the feat in 1978. In 1977 she represented GB&I on the Vagliano Trophy team against Continental Europe. During the time Mary Gorry was competing, Moira Smyth was an official and a regular spectator, so they knew one another vaguely.

And My Conclusion?

Looking back on it after a hundred years, the big question is: who beat Joe Gorry? Was it Wilson Smyth? Or the yelling ‘flag waggers’? Or did he beat himself? I have to admit that I think it was a combination of all three. It would be easy to accept his defeat by Smyth’s skill and his own obsessive deliberation. The yelling ‘flag waggers’ had no business being at a sporting event. Sadly, their partisan equivalents have emerged in recent years at the likes of the Ryder Cup, but these particular 1921 disrupters were intimidating at a time of great political tension.

While I have dispelled some aspects of the family legend, I retain the resentment at the interference of the bullies. I imagine that their intimidation increased my grandfather’s ‘fetish for deliberation’. Before a gallery of golf enthusiasts I think he would have scraped through. We cannot change history. I remain proud of Joe Gorry on his big day, even if it felt like failure to him.