It is impossible to imagine the mental state of John Jackson during his meeting with Dr. Dockeray 150 years ago this very day. John’s mind may have been in turmoil; it may have been numbed by grief. Whether Dr. Dockeray visited his farm in Kilmurry or John travelled the few miles to the village of Kiltegan is uncertain but the record shows that they were in contact on that day.

As well as being a physician and surgeon, Robert Dockeray was responsible for Kiltegan Registrar’s District [RD] within Baltinglass Superintendent Registrar’s District [SRD]. Even though Kilmurry was in the southern extremity of Baltinglass civil parish, it was in Kiltegan RD, so births and deaths occurring there were the Kiltegan registrar’s responsibility.

On 18 February 1871 John Jackson had the unspeakable task of providing information on the deaths on six of his children. I first became aware of the tragic deaths of the Jackson children in the summer of 1999, when I started transcribing the gravestone inscriptions in Rathvilly Church of Ireland churchyard. I was struck by the sad, stark wording of the Jackson stone and I wondered whether there might have been a house fire or an outbreak of typhus.

Shortly after seeing the gravestone, I was talking to a man I knew very well, John Farrar of Kilmurry. I told him what I had been doing in Rathvilly and he asked if I had seen the Jackson grave. I cannot remember whether he knew what had happened to the children but ever since I had the impression that they were struck down by a disease. The reason why he knew about the tragedy was that the children were his grandfather’s brothers and sister.

Like so many historical snippets I come across, the tragedy of the Jackson family moved to the recesses of my mind. A full twenty summers later I thought to complete my transcriptions in Rathvilly for publication in the tenth Journal of the West Wicklow Historical Society. When I came across the Jackson gravestone again, the memory resurfaced. Sadly, John Farrar was no longer with us by that time. I thought to obtain the death record of at least one child to see the cause of death but the publication deadline beat me to it. Last year, when the death records from the 1870s came online in the Civil Records database on Irishgenealogy.ie, I eventually looked at each of the Jackson children’s records.

The unfortunate children died of scarlatina, otherwise scarlet fever. This infection can develop in a person suffering from streptococcal throat, itself an infection caused by a contagious bacterium. Scarlatina is most common in children, circulating particularly in winter and early spring, and flourishing where people are in close contact. The sufferer would have a sore throat, a high fever and bright red rashes on the skin. It would appear that there was no general outbreak of scarlatina in the Baltinglass area in January / February 1871. No other deaths occurring in Baltinglass SRD in those months were recorded as having the same cause.

The gravestone lists the children in birth order and states that they died in the first week of February 1871. This case is a reminder that statements cast in stone are not always exactly true. It is also a reminder that official records are not always entirely accurate. The death records of all six children were registered on 18 February and the certified cause of death in each case was scarlatina. However, the dates of death were given from memory in a time of grief. The burial register of Rathvilly parish (which I have not checked) may well give some clarity.

The first child to pass away was Henry, who was almost two years old. The death record states that he died on 29 January, having had the infection for four days. Both Thomas (aged 8) and Mary (12) died on 31 January, having been five days infected. Samuel, recorded as four years of age (but who actually was five) died on 4 February after five days of infection. The following day Richard, aged ten, lost his struggle after six days. Finally, on 12 February, 14 year old Robert died of general dropsy after three weeks of scarlatina.

The Jacksons’ home was all but emptied of life in the space of about two weeks. The parents, John and Anne, along with their eldest child, Joseph William, were the only family members who definitely survived. There may have been one or two others but the Baltinglass C. of I. baptismal records do not survive for that time.

John Jackson of Kilmurry married Anne Jones of Holdenstown, just on the other side of the River Slaney, on 8 January 1852. Their wedding was in the old C. of I. parish church in Baltinglass, now part of the central ruins of Baltinglass Abbey. Their known children were born in this order: Joseph William (c1852-53), Robert (c1856), Mary (c1858), Richard (c1860), Thomas (c1862), Samuel (6 June 1865) and Henry (7 February 1868).

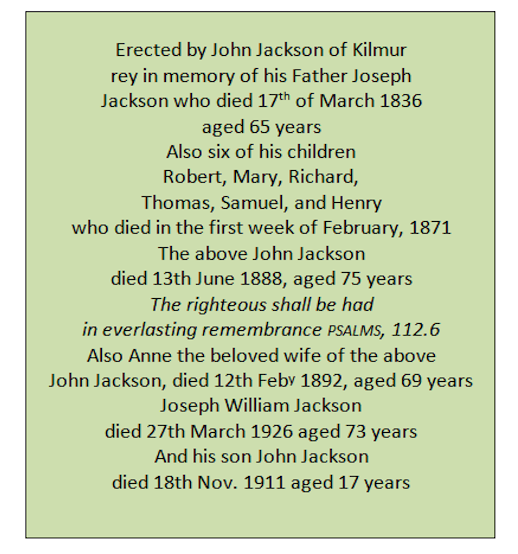

The gravestone in Rathvilly records four generations of the Jackson family. Covid restrictions prevented me from photographing it for this commemoration, so a faithful transcript must suffice. How parents, or even siblings, could emotionally come through such a shocking episode is difficult to comprehend. Perhaps it was their Christian faith that gave them the strength to bear the pain, believing that they would be reunited in Heaven. The quotation from the Psalms may be a key to their way of coping with the situation:

‘The righteous shall be had in everlasting remembrance’.

Today, 150 years after this tragedy, the Jackson children and their grieving family are remembered in the little corner of the universe where they once lived in this realm.