On 16 December 2022 I sold my last copy of Baltinglass Chronicles 1851-2001. What that means is that it’s now more or less out of print after a sixteen-year span. On 14 December I received an order for a copy on the Wicklow Marketplace. That went to someone in the immediate area of Baltinglass. Two days later I received my last order – I despatched it on Saturday to Heather in Cincinnati. In the past sixteen years Baltinglass Chronicles has travelled to various parts of the world.

As of Monday afternoon there were two copies available to purchase in Burkes in Main Street, Baltinglass, but when they’re gone there are no unsold copies available anywhere in the world, or even the universe! Checking online I found a ‘new’ copy for sale on Amazon.it for €68. That’s more than three times the ordinary retail price. The cheapest used copies I saw were for just under €39.

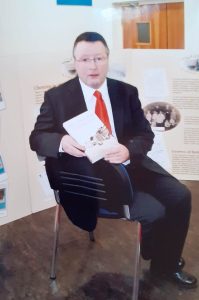

I remember the day of the launch of the book. I’m not quite sure of the date but it was a Saturday afternoon in November 2006. I was all suited up and ready to go. Then I was asked by a friend to carry her heavy baby across the bridge to be deposited for the while in Mill Street. I was in a panic to get back and I was thinking that I’d be rightly dishevelled before the event even started.

The launch was in Baltinglass Library. I was quite overwhelmed at how many showed up. I had unbelievable support from the people of Baltinglass as well as family, friends and colleagues. The official proceedings were opened by Eoin Purcell, then publishing manager for Nonsuch Ireland, which is now subsumed into The History Press Ireland. I see that Eoin is now Head of Amazon Publishing UK + DE. Baltinglass Chronicles was officially launched by my friend Aideen Ireland, then President of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland.

At some point before or after Aideen I had to make a speech. I remember saying that my Gorry grandfather opened his second ‘medical hall’ in 1906, in Baltinglass, and that my father came to live here in the early 1930s. I also said that in the late 1990s a Baltinglass native, who lived practically all her life in Dublin, said to me ‘It’s strange that you’re so interested in the history of Baltinglass, and your family runners-in’. Sixty or even ninety years is not enough to be associated with Baltinglass. To be called ‘a blow in’ is mildly offensive but to be called ‘a runner-in’ is a downright insult!

I remember particularly mentioning the young Baltinglass men who died in the Great War and naming one or two of those listed in my book. I mentioned Jimmy Murray, calling him my agent, as he was so encouraging about future sales and indeed he sold a huge number of copies.

I remember mentioning that (the now late) Patsy Doody once said to me that the McDermott girls, my mother and her two sisters, were lovely ladies and that they came to Baltinglass and each of them married a man with a corner house. That got a good laugh. It’s true – Mum and Auntie Nora married men with corner houses at the top of Church Lane, while Mary married into ‘The Hollow’, once a corner house and now partly the entrance to Gillespie’s SuperValu. The McDermott girls were true blow-ins.

It was lovely to have my aunt Joan Gorry present: it was her father who opened his branch ‘medical hall’ in Baltinglass in 1906. It was equally lovely to have an assortment of my Harbourne and Heydon cousins there as well, the progeny of the other two corner houses. All my siblings were present, along with most of my immediate family, local friends, and friends who were colleagues from genealogy. Seeing a long queue of people in front of me waiting to have their copies signed was something I’ll never forget. Baltinglass people were truly wonderful in their response to my project. Looking back at it now, I feel greatly honoured that they were so supportive. I don’t know who the oldest person attending the event was but I do know that four year old Nita Bajrami was the youngest.

Back in 1950 a dreadful, ugly incident took place in Baltinglass that left a bad aftertaste that lasted to the time of my youth. It was a politically motivated dispute about the appointment of a new sub-postmaster to the town. Two families, the Cookes and the Farrells, were reluctantly centre-stage in this drama that became known as the ‘Battle of Baltinglass’. Fifty-six years later I wrote extensively about ‘the Battle’ in my book. At the launch I had the pleasure of introducing Nan O’Sullivan (first cousin one removed of Helen Cooke) to Tom Farrell (brother of Michael Farrell). I left them having a friendly chat.

On the night of the launch I had a phone call from someone who had been reading the book all evening. That was a great compliment. Later, someone old enough to know the situation told me that I had been fair and balanced in my coverage of ‘the Battle’. Another person told me that they had bought multiple copies to send to family members. Another person told me recently that they were reading the book for the eleventh time. Kathleen Wall was one of several people who gave me valuable information. She had a sharp mind and a wonderful memory. Mrs. Wall died nearly a year ago. I was talking to her son just last week and he mentioned how she prized her signed copy of my book. These are reactions that collectively make me feel very emotional. What beautiful responses to something I created! I’m so grateful to all who took the time to contemplate my writing.

The Development and “Life” of Baltinglass Chronicles

Two years before I was born Claude Chavasse came to Baltinglass as minister of Baltinglass Church of Ireland group of parishes. In my earliest memories Canon Chavasse was an old man and I was a little boy. He lived in the Rectory, at the bottom of Church Lane, and I lived at the top of Church Lane. I remember his cheerful face as he passed up the lane in his Morris Minor (or at least I think it was that – I’m no good with cars). He retired when I was about ten and the following year his book The Story of Baltinglass appeared. It was (and still is) a prized possession of mine. I revered that little book and I never really thought that there was need for another on Baltinglass, though he covered the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in just a few pages.

Coming up to 1 January 2001, the real beginning of the new millennium, I thought that a street directory / list of adults in Baltinglass and surrounding townlands would be a worthwhile record for posterity. This was because the regular census was postponed due to the outbreak of Foot and Mouth Disease. I printed hundreds of forms to be distributed to households, asking for details. My friend Majella Murphy helped greatly in their distribution and collection. I had a box in my sister’s pharmacy where people could return their forms. I thought all this was quite normal until afterwards, when I realised the big ask I made and the terrific response I received. A handful of households declined to complete the details. The overwhelming majority co-operated.

Then I had the idea to compare 2001 with 1901, using the census of that year and the Valuation Office revision books. Then I included 1951 and 1851. That involved a huge amount of research but, when I thought about it, it was just a framework with no substance. So, I started writing the historical innards. I had no thought as to how it might be published. “God will provide” was my mantra. Eventually Nonsuch Publishing contacted the West Wicklow Historical Society. I responded, saying that I was writing this tome which wasn’t within their parameters. Eoin Purcell arranged to meet me and he offered to publish it for me. I might still be writing it now if it weren’t for Eoin giving me a deadline. The last few weeks of writing were torture but I got it finished.

Nonsuch decided to go for a print run of 1,500 but in the end there were 1,700 books produced. Selling the full 1,700 in 16 years doesn’t sound much, but this wasn’t a novel or a national history – it was a local history about a small Irish town. There were hundreds sold in the first few months, in no small part due to Jimmy Murray. Thereafter they trickled slowly out to local households or far flung places. In more recent times, when I was in possession of almost all unsold copies, I joined Rachel Kane’s online Wicklow Marketplace and there I sold my last copies.

Nostalgia

Sixteen years on, I look back to the day that Baltinglass Chronicles was launched with mixed emotions. It was a memorable day for me, made special by the interest and generosity of the people of Baltinglass. But looking back is tinged with sadness: some individuals who were very dear to me are no longer here. Many townspeople who embraced my project, filling in those forms or buying copies at the launch, are gone from us. I suppose that’s part of the story of a small town. Time passes, people leave us and others come along. Claude Chavasse and Paul Gorry and all the people who contribute to the tapestry are just passing through; Baltinglass is a continuum.

A very vivid description of the launch Paul. Brought it all back to me. I had forgotten that you had introduced my mother to Tom Farrell. I’m sure those copies in Burkes will not be there for long!